Drawing the Line: Media Freedom, Public Accountability, and the Sakaja Ruling

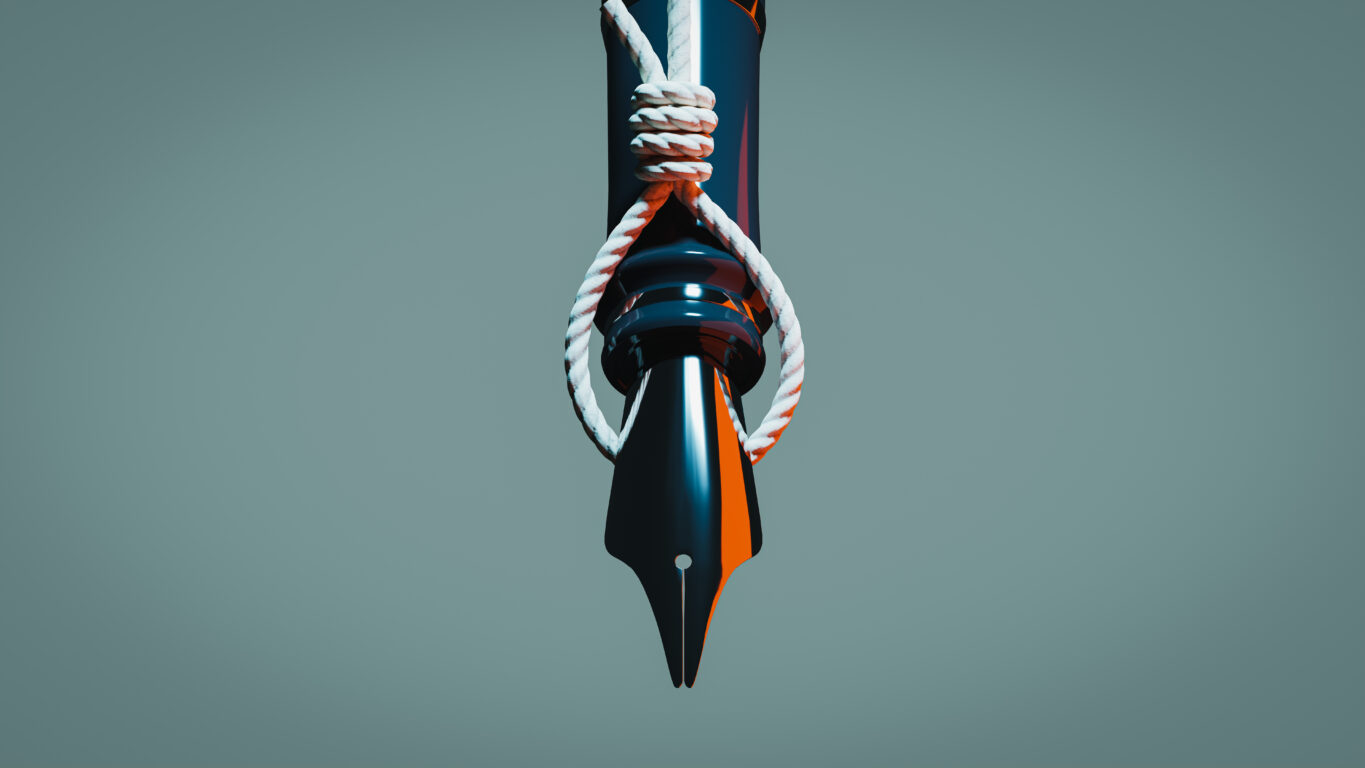

Few areas of law are as contested or as revealing of a nation’s democratic maturity as defamation. It is where individual dignity collides with the collective right to know. At stake are not just personal reputations but also the boundaries of public discourse, the health of journalism, and the resilience of constitutional freedoms. Kenya’s recent High Court decision in Sakaja Arthur Johnson vs Nation Media Group Limited and Two Others (Civil Case No. E169 of 2025) has thrust this tension back into the national spotlight. This has prompted a deeper examination of how far the law should go in protecting individuals from reputational harm without stifling legitimate scrutiny.

The case is emblematic of the challenges facing modern democracies. In an era where information spreads instantly, the lines between fair reporting, political contestation, and defamation are increasingly blurred. Public officials, in particular, walk a fine line between being victims of falsehoods and subjects of necessary accountability. The Sakaja decision, therefore, stands as more than a legal determination; it is a mirror held up to Kenya’s evolving relationship with the press and the public’s right to know.

The Sakaja Case and Its Broader Context

On 30 September 2025, the High Court in Nairobi dismissed an application by Nairobi Governor Johnson Sakaja seeking an injunction to restrain Nation Media Group from publishing any stories linking him to “goons” alleged to have disrupted the 17 June 2025 protests. The Governor contended that an article titled “How Chaos Was Planned” defamed him and wanted the Court to bar any similar future reporting. Justice Prof. Nixon Sifuna refused to grant the order, ruling that pre-trial gag orders against established, regulated media houses are exceptional and should be issued only where there is clear and imminent harm.

The Court treated the matter not merely as a personal dispute but as a constitutional test of principle: the delicate balance between Article 28’s protection of human dignity and Article 34’s guarantee of media freedom. The decision underscored that public office comes with heightened exposure to scrutiny, and that efforts to pre-empt legitimate reporting threaten the core of democratic transparency.

Judicial Restraint and Constitutional Balance

Justice Sifuna grounded his reasoning in the well-known Giella vs Cassman Brown framework, which comprises the existence of a prima facie case (when the evidence presented is sufficient to support a verdict), the inadequacy of damages, and the balance of convenience. He went further, situating these principles within the constitutional order that emerged after 2010. In media and defamation cases, he argued, the question cannot be purely procedural. It must account for the wider public interest, the freedom of expression guaranteed to the press, and the danger of prior restraint in an open society.

Justice Sifuna grounded his reasoning in the well-known Giella vs Cassman Brown framework, which comprises the existence of a prima facie case (when the evidence presented is sufficient to support a verdict), the inadequacy of damages, and the balance of convenience. He went further, situating these principles within the constitutional order that emerged after 2010. In media and defamation cases, he argued, the question cannot be purely procedural. It must account for the wider public interest, the freedom of expression guaranteed to the press, and the danger of prior restraint in an open society.

The Court rejected the notion of a rolling or speculative injunction based on fear of future harm, emphasising that damages and corrections remain adequate remedies. It also acknowledged the layered accountability mechanisms within the mainstream media, editorial oversight, fact-checking, and compliance with the Media Council’s Code of Conduct as structural safeguards that make heavy-handed judicial intervention unnecessary. The message was clear: courts are not censors, but guardians of balance.

Policy Considerations: The Defamation Framework in Context

Kenya’s defamation law sits on foundations that predate the constitutional era. The Defamation Act (Cap 36), enacted in 1970, remains the central statute governing civil defamation. It reflects a traditional common law view that focuses on protecting reputation through damages and injunctions, with little regard for constitutional standards or the public’s right to information. The Act was never updated to align with the 2010 Constitution, which fundamentally altered the legal landscape by embedding freedom of expression and media independence under Articles 33 and 34.

Before 2010, Kenya also criminalised defamation under section 194 of the Penal Code. This punitive approach was a colonial inheritance, treating defamatory statements as crimes against the State rather than private civil wrongs. That position was overturned in 2017, when the High Court in Jacqueline Okuta & Another vs Attorney General & Another declared criminal defamation unconstitutional. The ruling recognised that criminal sanctions for speech were incompatible with a democratic society committed to open discourse. What remains today is a civil law model grounded in the 1970 Act, one that has not kept pace with constitutional or technological change.

The policy challenge lies in this mismatch. The Defamation Act offers slow and costly redress through civil suits, while the Media Council Act, 2013, establishes a parallel complaints mechanism limited to ethical breaches. The Council can recommend retractions, apologies, or corrections, but it cannot award damages or enforce its decisions. This leaves litigants oscillating between the courts and self-regulatory mechanisms, with neither providing swift, effective, and constitutionally balanced relief.

To address this gap, targeted reforms are necessary. At the outset, there is a need to update the Defamation Act to reflect constitutional standards, recognising freedom of expression as a fundamental consideration in civil proceedings. Secondly, fast-tracking defamation hearings for matters of high public interest to provide timely resolutions is fundamental. These would need to be complemented by anti-Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (anti-SLAPP) provisions to prevent misuse of defamation suits as political tools to silence journalists and activists. These steps would align legal remedies with modern realities and reduce the temptation to seek pre-trial gag orders, such as the one rejected in the Sakaja case.

Strengthening Media Accountability

Justice Sifuna’s ruling reaffirmed trust in the formal media’s internal checks. However, such trust must be reinforced by transparency. Newsrooms should maintain clear editorial documentation, especially for stories involving public officials or sensitive investigations. Timely correction mechanisms and published right-of-reply policies can reduce the need for litigation and demonstrate a commitment to fairness.

The Media Council of Kenya can also play a stronger role by publishing regular transparency reports on complaints handled and corrections issued. Public confidence in journalism is sustained not only by freedom but also by accountability. As the digital ecosystem expands, Kenya must extend these principles to online platforms and citizen journalists, ensuring that ethical standards apply consistently without weaponising regulation.

A Democratic Lesson in Restraint

The Sakaja vs Nation Media Group case decision captures a defining constitutional moment. It serves as a reminder that the law’s purpose is not to silence dissent, but to preserve the space where truth and accountability coexist. Defamation law must protect individuals from reckless falsehoods, but it must never become an instrument for suppressing legitimate inquiry. The 2010 Constitution transformed Kenya from a state that policed speech to one that protects it as a cornerstone of democracy.

In affirming this, Justice Sifuna’s ruling delivers a broader message: power must remain open to scrutiny, and courts must resist the temptation to guard it from criticism. The health of Kenya’s democracy depends on an equilibrium where reputation and free expression are not opposing forces but complementary pillars of an open society.