Part 6: Sports and Entertainment Services

NAVIGATING THE TAX LANDSCAPE FOR THE SPORTS & ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRIES IN KENYA

Written by Sarah Ochwada & Stacey Bonareri

Taxes levied on sports people, entertainers and gamers relate to gains derived from their sources of income which vary from contractual sums, financial awards, bonuses, content creation and licensing of Intellectual Property (IP) assets. There are various categories of tax levied upon taxpayers in Kenya for example: Income Tax, Value Added Tax (VAT), Withholding Tax, Import Tax, Corporate tax among others.

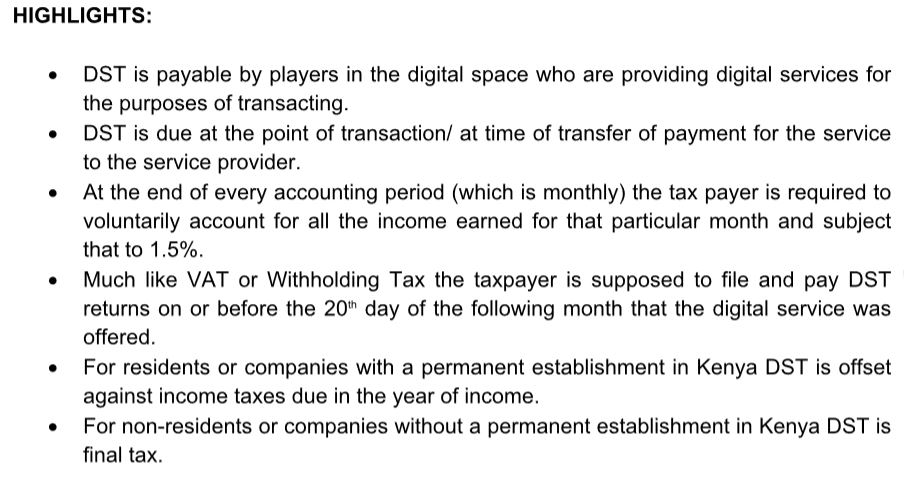

Kenya’s latest form of taxation is the Digital Service Tax (DST) which came into force on 1st January 2021. It imposes a 1.5% tax on the gross transaction value of services provided on digital platforms operating within the “digital-market place” which has been defined in the VAT Act as “a platform that enables the direct interaction between buyers and sellers of goods and services through electronic means”.

DST has caused ripples across different business sectors particularly the creative industry who rely on digital platforms to showcase their talent and sell their tickets or merchandise.

This article will break-down the types of taxes due in the sports and entertainment industries as well as a roadmap on how to assess what is owed by the various stakeholders.

TAXATION IN THE ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY

The entertainment industry as a whole is a service-driven industry comprising musicians, film-makers, free-lance content-creators, artists, actors, poets, fashion designers, authors, publishers, video-game developers who create products or services for enjoyment by other people. The taxation of individuals and entities within this sector is guided primarily by Income Tax regulations (for income accrued over the course of a year) and VAT regulations (for income derived from sale of entertainment products and services). It’s worth noting that over and above charging VAT for supply of services, Companies are required to register for and file VAT returns if their income threshold is in excess of 5 million Kenya shillings annually.

For instance: a musician who wishes to stage a concert and sells tickets for that concert is required to pay VAT on the gross value of the tickets sold as s/he is providing the service of entertainment. If the musician sells physical albums or CDs of his/her music, then such items also attract VAT per item sold. Moreover, musicians benefit from royalties from licensing or public performance of their copyrighted musical works which are subject to a 5% Withholding Tax for residents and 20% Withholding Tax for non-residents payable by the person/ entity collecting the royalty on their behalf.

For instance, the Music Copyright Society of Kenya (MCSK) and any other Rights Management Organization should Withhold 5% or 20% of the total amount payable to the artist and remit the same to the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA). Safaricom’s Skiza, being a subscription-based ring-back tune platform should also remit withholding tax from Royalties due to creators whose works are regularly subscribed to and downloaded off their platform. Royalties generally include gains made from the use or licensing of IP – e.g. copyrighted works, trademarks, data, image rights, personality rights.

However, the recent pandemic lockdown has seen entertainers making more use of the digital space to reach their audiences and create new streams of income. As a result, the entertainment industry has embraced technology at a larger scale and is relying on digital platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, Spotify and Mookh to store, share and distribute their content for download or streaming.

This is where the Digital Service Tax comes in; the DST is charged to the digital service provider who accrues income from content which is placed on a digital platform. Since both the platform provider and the content creator derive income from the content which is placed on the platform, then they are each individually subject to 1.5% DST. For instance, Kenyan YouTubers who use Google Ad-sense to monetize their channels are subject to 1.5% tax for income derived from their content. Google, is also subject to 1.5% tax on the same content as they provide the digital marketplace (YouTube) on which the content is hosted.

The catch is whether KRA can effectively police and enforce DST on internet users. No sovereign State can lay claim or purport to control the digital space. Even the term “digital marketplace” is debatable. However, the Kenyan government plans to go around this issue by applying the tax on income from services derived from Kenyans, or accrued in Kenya from a digital marketplace. This means that as long as persons or entities in the digital space are providing services online which generate income through a Kenyan creator then both the creator (as a Kenyan resident or non-resident) and the platform provider (whether or not the entity is permanently based in Kenya) will each pay 1.5% of the gross transaction value.

The same tax system applies to content creators who post their work on digital market spaces but do not directly monetize their channels for income. They instead open PayPal or Patreon Accounts where viewers can become their patrons by donating to them directly. In this instance, the Kenyan tax laws still deems such “donations” as income unless the content creator can prove that the funds are for charity and that such charity applied for and received a tax exemption. In any case, even charitable organizations which enjoy tax exemption status are still required to pay some tax on the funding they receive. The grey area may be religious institutions which have started streaming their worship services online since the onset of the Pandemic, but even they may not easily escape DST.

There are also content creators who post their content on popular platforms but derive their earnings offline for example, content creators who are paid by companies for product reviews or product placement but do not derive income directly from the platform provider. The DST regulations seem to be silent on the following classes of people: a) click and mortar creators who have digital stores, market their products and services online, but close the sale, receive payment and deliver offline; and b) brick and mortar creators who market their products online but have a physical location where buyers come to buy goods and services; and c) hybrid creators who have both physical and digital stores, market their products and services online, but close the sale and receive payment via digital payment channels such as Payapal or Lipa na Mpesa.

TAXATION OF THE SPORTS INDUSTRY

Sports is a very broad area and finding the point of taxation of such can be difficult. There are various sources of income generated by a sportsperson though their activities aside from their contractual earnings, competition bonuses and commercial sponsorships deals. It is, therefore, essential to understand how such sports persons derive their income to understand their tax obligations.

A good example that can fit within our Kenyan income tax regime is that of a Football player who can be viewed as an employee of a particular football club and hence subject to P.A.Y.E (Pay as You Earn). A professional track athlete, however, is not an employee of a club but derives income from winnings and endorsement deals but depending on the jurisdiction of the competition or the entity paying the athlete he/she may suffer double taxation of their income.

The concept of double taxation is applied where an athlete having competed in a country other than his own is taxed on the amount earned and subsequently, taxed once again in his or her own country. The amount to be given on winnings is first subject to the taxation regime of the country where the event is held. In addition, the athlete is also required to pay taxes in his/her country of residence from the earnings of such an event. In order to remedy this, countries enter into double taxation treaties in order to offset and grant relief on the taxes to be paid.

Additionally, for equipment-reliant sports such as shooting, archery, weightlifting, table-tennis, martial arts etc. the cost of acquisition and transport of such equipment can be an economic burden on the sportsperson, sports club or federation.

Depending on the sport equipment to be imported, the item incurs import duty tax in addition to import declaration fees are levied on the goods. For instance, for professional gamers a PC or console is required to train and practice skills in a particular game. A console, such as PlayStation 4 retails at Kshs. 45,000 in Kenya. Sony recently released a new console that retails at a price range of Kshs. 55,000 to Kshs. 65,000 depending on where you purchase it. In contrast the price of a gaming PC or laptop retails from Kshs. 105,000 which is slightly higher than console. Therefore, a dealer who primarily deals with such equipment incurs a lot to have it available in Kenya.

In the end, the high taxes levied means the pieces of equipment will be priced at high amounts, and purchase of the same will cost an arm and a leg as the importer has a reverse VAT obligation to pay for the equipment. Even if the sporting equipment is donated for free by an organization from outside Kenya the import duties and VAT are still payable on the value of the goods. Hence the taxes imposed leave many sportspeople, clubs and federations unable to pay for and acquire their goods which are necessary to play the sport. In some cases, the equipment attracts astronomic storage fees at the port and are subjected to auction if they remain unclaimed.

Sarah Ochwada is a Retired Runway Model turned Archer, Advocate, Arbitrator and Lecturer. She is a pioneering Kenyan Entertainment Lawyer and is the 1st black African woman to hold a Masters’ Degree in International Sports Law. She was an Adjunct Lecturer at Strathmore University Law School based in Nairobi, Kenya where she has taught undergraduate and executive courses in Sports & Entertainment Law, Media Law, Consumer Protection Law, and Fashion & Beauty Law. She is also a visiting lecturer at ISDE Law and Business school where she has taught International Sports Law at their Madrid Campus, Spain and at Wolfson College, Cambridge, UK. She is Legal Counsel for the National Olympic Committee of Kenya (NOCK), and has been appointed as Arbitrator for the Qatar Sports Arbitration Foundation (QSAF), Football Kenya Federation (FKF), Athletics Kenya and Cricket Kenya. Sarah is the CEO for Centre for Sports Law a non-profit providing pro-bono legal services for the sports sector – specifically representing athletes before the Sports Disputes Tribunal and the Court of Arbitration for Sport. Sarah runs her own private practice – SNOLEGAL Sports & Entertainment Law- a cyber-legal firm focusing on emerging and cutting edge areas of law.

Stacey Bonareri is an Advocate to the High Court of Kenya. She is a Resident Trainee in Interactive Entertainment, E-Sports and Technology at SNOLEGAL Sports and Entertainment Law- a boutique firm. Her interests lie at the intersection of sports and technology but she also has a keen enthusiasm for areas relating to sports governance, policy and the business of sports. She has a key interest in data protection and privacy law with particular interest in Fintech and Start-ups. She handles compliance with a fintech firm based in Ghana called Appruve Technologies. In her spare time, she codes and was part of the winning team at the Nairobi 2020 Africa Law Tech Festival Legal Hackathon.