Moody Ratings and Kenya’s Path on a Fiscal Tightrope

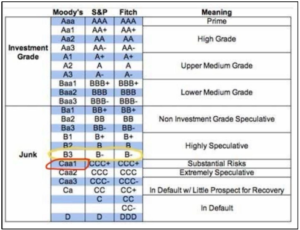

Moody’s Ratings recently downgraded Kenya’s local and foreign currency long-term issuer ratings and foreign currency unsecured ratings to Caa1 from B3. This rating largely paints a negative outlook for the country’s fiscal status.

The downgrade is significantly reflective of a diminished capacity to implement revenue-based fiscal consolidation that would improve debt affordability and place debt on a downward trend. Fiscal consolidation connotes government efforts to reduce its budget deficit, the gap between spending and revenue.

For a very long time, and even via the Finance Act, 2023, the government relied on revenue-based consolidation, which focuses on increasing tax collection or introducing new revenue streams, and expenditure-based consolidation, which prioritises cutting spending, as the basis for its fiscal consolidation strategies.

The decision to withdraw the Finance Bill, 2024, and the ensuing decision to not pursue planned tax increases and instead rely on expenditure cuts to reduce the fiscal deficit represents a significant policy shift with material implications for Kenya’s fiscal trajectory and financing needs. The shift to expenditure-based consolidation presents a new frontier for the country.

Revenue-based consolidation, while politically challenging, offers a more sustainable path in the long run. Increased tax revenue provides a predictable and reliable source of income to service debt and fund essential government services. Conversely, expenditure-based consolidation, relying on spending cuts, can be more immediate but carries significant risks.

This policy shift is the sole reason behind the downgrade by Moody’s.

The Downgrade: What it Means and the Consequences

Moody’s downgrade signifies a significant loss of confidence in Kenya’s ability to manage its debt burden. The Caa1 rating falls within the “junk” category, indicating a very high risk of default on loan repayments. (See figure below)

In the face of heightened social tensions, the government may not be able to introduce significant revenue-raising measures in the foreseeable future. This portends a scenario that would see the fiscal deficit narrow more slowly, with Kenya’s debt affordability remaining weaker for longer. In turn, larger financing needs stemming from a wider deficit increase liquidity risk against more uncertain external funding options. Similarly, continued financing needs may result in the need to borrow more. Borrowing comes with costs, and this would further amplify liquidity risks.

More importantly, slower fiscal consolidation would risk constraining external funding options even more, including diminishing support from multilateral creditors, which have been the largest source of external financing since 2020. An increment in larger financing needs would also risk reducing domestic appetite for government securities, which would challenge its ability to continue servicing domestic debt.

This downgrade translates to several negative consequences for the country:

- Firstly, the cost of borrowing will skyrocket. Investors, wary of the increased default risk, will demand higher interest rates on Kenyan government bonds. This will strain the government’s budget further, limiting resources available for critical investments in infrastructure, healthcare, and education.

- Secondly, foreign direct investment (FDI) is likely to take a hit. Businesses often use credit ratings as a gauge of a country’s economic stability. A downgrade signals a risky environment, deterring international investors from setting up shop in Kenya. This not only reduces foreign capital inflow but also stifles innovation and job creation.

The Domino Effect on Corporates

The ramifications of the downgrade extend to Kenyan corporates as well.

First, it will potentially result in higher borrowing costs. Increased government borrowing, particularly domestic borrowing, will crowd out private-sector credit. Banks may become more cautious in lending, making it more expensive for businesses to access financing for expansion or working capital needs.

Similarly, it may result in the depreciation of the shilling. A loss of investor confidence often leads to a depreciation of the local currency. This can make imports more expensive, squeezing profit margins for businesses that rely on imported raw materials. Conversely, exporters might benefit in the short term, but a weaker currency can lead to uncertainty and hamper long-term planning.

The potential impact on consumer spending also exists. A potential economic slowdown due to lower investment and government spending will likely translate into reduced consumer spending. This can hurt businesses across all sectors, particularly those catering to the domestic market.

Conclusion: Navigating the Tightrope

The government faces a delicate balancing act. While expenditure cuts offer a quick fix to the deficit, they can stifle economic growth in the long run. At the core of the navigation strategies should be tax reforms and public-private partnerships.

Tax Reform, not Tax Increases, should be the first port of call. The government needs to look for ways to broaden the tax base by bringing more individuals and businesses into the formal sector. Streamlining tax collection processes and tackling corruption remain imperatives in the journey towards improving revenue generation without resorting to unpopular tax hikes.

Additionally, there is a need to continue leveraging private sector expertise for infrastructure development projects. This can free up public funds while improving project efficiency and delivery.

It cannot be reiterated enough that the path to fiscal consolidation requires transparency and collaboration. The government needs to articulate a clear and comprehensive plan to address the debt challenge. Open communication with stakeholders, including the private sector and civil society, will be crucial in building trust and ensuring policy measures are well-calibrated.

The current situation presents a stark challenge for Kenya. However, with a focus on long-term sustainability and a willingness to engage in difficult conversations, the country can navigate through this turbulent period and emerge with a stronger and more resilient economy.