Main Feature: World Economic Outlook Report 2023: Insights into the rocky path to recovery

What is the IMF?

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was established in 1944 in the aftermath of the Great Depression in the 1930s. At the founding stage, the membership of the IMF comprised 44 member states. The membership has grown to a near-global status, with membership being 190 countries. These member states govern the IMF and the IMF is entirely and fully accountable to its members.

IMF’s members pay capital subscriptions in quotas. Upon registration, each member is assigned a quota that is determined on a broad basis of the relative position of the country in the global economy. This forms the major resource bank for the IMF. Additionally, countries can also borrow from the pool collected by the IMF, if and when they fall into financial difficulty.

The core functions of the IMF include:

(a) Issuance of loans, including emergency loans, to members in financial uncertainties. The objective for this is to facilitate members building their international reserves, stabilisation of currencies, and restoration of the economy as the affected country resolves its underlying problems.

(b) Provision of technical assistance through capacity-building programmes, as a way of helping countries tackle cross-cutting issues, such as income inequality, gender equality, corruption, and climate change.

(c) Monitoring of the international monetary system and global economic situation in order to identify risks and make recommendations, in terms of policy, for growth and financial stability.

Fundamentally, the IMF also takes periodic health checks on the economic and financial policies of its member states, identifies the risks emanating therefrom, and issues advisories to these member states on the need for possible policy adjustments.

The World Economic Outlook, 2023

In furtherance of its function to monitor the international economic situation, identify risks, and advise members on how to respond and mitigate potential setbacks and drawbacks, the IMF publishes an annual report detailing the global economic outlook. This Report is usually exhaustive and highlights global economic issues, the reasons behind the prevailing global economic conditions, and what the situation portends for nations.

- Global Projections and Prospects

The World Economic Outlook, 2023 Report has since been published. The Report has four chapters each speaking to different components of the political economy. From a general perspective, the report paints a path of global recovery but appreciates that the path is not smooth and seamless, but is rather rocky. The report underscores that the global economic outlook is again uncertain as a result of the turmoil being experienced in the global financial sector. The report further adds that this uncertainty has been exacerbated by the war in Ukraine and the far-reaching effects of Covid, three years later, on the global economic dynamics.

This dispels the earlier tentative signs in early 2023 that the world economy was destined for a soft landing. The major factor here is that while inflation is declining, central banks have been forced to adjust interest rates upwards, and the tight labour markets and underlying price pressures have proven to be sticky notes for the global economy. The tumult in the financial sector has not made it any easy, despite food and energy prices steadily going down, as the banking sector which plays a key role in the movement and injection of cash in the economy, has become vulnerable due to the turmoil. The noticeable fear is that as a result, fears of contagion have risen across the broader financial sector, including nonbank financial institutions, which has massive ramifications on the general economic outlay.

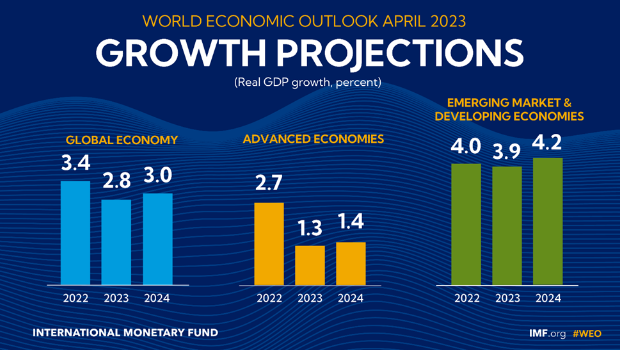

In terms of projections, the IMF contends that (See Figure 1 below):

- The baseline forecast is for growth to fall from 3.4 percent in 2022 to 2.8 percent in 2023, before settling at 3.0 percent in 2024. Advanced economies are expected to see an especially pronounced growth slowdown, from 2.7 percent in 2022 to 1.3 percent in 2023;

- The other alternative scenario, that is indeed plausible with further stress in the financial sector, is that global growth will decline to about 2.5 percent in 2023 with advanced economic growth falling below 1 percent.

iii. Global headline inflation in the baseline is set to fall from 8.7 percent in 2022 to 7.0 percent in 2023 on the back of lower commodity prices but underlying (core) inflation is likely to decline more slowly. Inflation’s return to target is unlikely before 2025 in most cases.

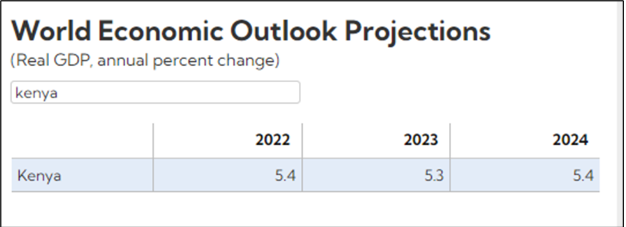

For Kenya, growth is projected to stagnate at 5.4 percent in 2023, as it was in 2022 and the same is projected to increase to 5.4 percent in 2024, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 1: Global Economic Growth Projections, IMF 2023

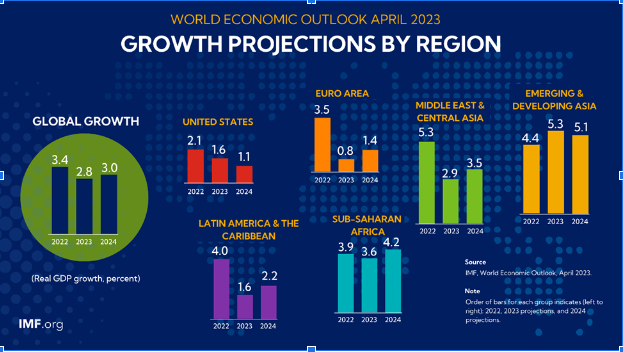

Figure 2: Regional Progressions, IMF 2023

Figure 3: Kenya’s Economic Projections

2. The Natural Rate of Interest: Drivers and Implications for Policy

Swedish Economist, Knut Wicksell in his book “A Treatise for Money” defined natural rate of interest as “a certain rate of interest on loans which is neutral in respect to commodity prices and tends neither to raise nor to lower them”. To contextualize it further, it is perceived as the real interest rate that neither stimulates nor contracts the economy. The natural rate of interest is a constant baseline used by economists to guide both monetary and fiscal policy and is also a key determinant for debt sustainability.

The IMF notes that:

- Far from ideal, the natural rate of interest has declined, across the past four decades, in most advanced nations as well as in emerging markets. There are idiosyncratic factors to explain the cross-country differences but to better understand the synchronized decline more needs to be done around demographic transitions and productivity slowdowns.

- Global drivers have also been important determinants but on balance have had a limited impact on net capital flows and corresponding natural rates in advanced and emerging market economies.

iii. Country-specific natural rates of interest are projected to converge in the next couple of decades. Based on conservative assumptions on demographic, fiscal, and productivity developments, it is anticipated that natural rates in large emerging market economies will decline, gradually converging toward the low and steady levels expected in advanced economies.

- As inflation returns to target, the effective lower bound on interest rates may become binding again. Post-pandemic increases in interest rates could be protracted until inflation is brought back to target.

- Despite increased fiscal space, many countries will have to consolidate. While low natural rates may ease pressure on fiscal policy, they do not negate the need for fiscal responsibility. Important government support during the pandemic has strained public accounts, requiring some budget consolidation to ensure long-term debt sustainability. Various paths to deficit reduction are open, but delaying action will only make the required steps more drastic: Larger public debt tends to crowd out private investment and erode the appeal of safe and liquid government debt.

Overall, the IMF analysis paints a picture of an inflationary episode epitomized by the decline in the natural rate of interest and varying cross-border interest rates. The comfort though is that this is an episode that will pass and interest rates are likely to revert toward pre-pandemic levels in advanced economies. It is important to highlight that for the level of closeness to revert to the pre-pandemic rates depends on whether alternative scenarios involving persistently higher government debt and deficit or financial fragmentation materialize. For that reason, fiscal authorities, based on IMF advisory, over the long term, need to put in place fiscal adjustment plans aimed at stabilizing or reducing debt-to-GDP ratios.

3. Tackling the Soaring Debt Levels

As a result of the unprecedented Covid-19 pandemic, public debt as a ratio to GDP soared in various countries globally. This situation is expected to stay at an elevation, creating a real challenge for policymakers, more particularly with the soaring levels of real interest rates globally.

In order to come down to earth and control these soaring levels of debt as a ratio of the GDP, the IMF having conducted an econometric analysis and complimenting that with a review of historical experiences, proposes:

- Adequately timed and appropriately designed fiscal consolidation measures need to be put in place by countries, as they have a high probability of durably reducing debt ratios.

- For countries in debt distress, a comprehensive approach that combines significant debt restructuring—renegotiation of terms of servicing of existing debt—fiscal consolidation, and policies to support economic growth is of significance in offering long-lasting solutions to reducing debt ratios.

iii. Nations need to put in steps to spur economic growth as economic growth and inflation have historically contributed to reducing debt ratios.

4. Geoeconomic Fragmentation and Foreign Direct Investment

The war in Ukraine has resulted in disruptions in the supply chain. The rising geopolitical tensions have made it even worse, causing the need to scrutinize and probe, as a matter of policy debate, the risks and potential benefits and costs of geoeconomic fragmentation. This consideration also captures how such fragmentation can affect the outlay of foreign direct investment (FDI) and, in turn, how FDI fragmentation can affect the global economy.

It is clear to see that FDI flows are now increasingly concentrated among geopolitically aligned countries, particularly in strategic sectors. Several emerging markets and developing economies are highly vulnerable to FDI relocation, given their reliance on FDI from geopolitically distant countries.

In the long term, FDI fragmentation arising from the emergence of geopolitical blocs can generate large output losses, especially for emerging markets and developing economies. Multilateral efforts to preserve global integration are the best way to reduce the large and widespread economic costs of FDI fragmentation.

Consequently, the IMF suggests that there is a need to carefully balance the strategic motivations behind reshoring and friend-shoring against economic costs to the countries themselves and to third parties, including through multilateral consultations to reduce uncertainty for bystanders.