Kenya’s innovative approach to financing entrepreneurs: A deep dive into credit guarantee schemes.

Credit guarantee schemes (CGSs) are a form of financing for SMEs that emerged in Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries, spearheaded by civil society and the private sector as a way to proffer credit to smaller businesses that may not otherwise qualify for credit from Banks due to factors like insufficient collateral, high risk, and information asymmetry. Lenders extend credit to entities deemed too risky by conventional financial institutions while simultaneously mitigating their risk in case of default. Should the entity default, the lender has a safety net as they can recover the value of the guarantee.

Many kinds of CGSs have evolved. Kenya established a Public Guarantee Scheme in 2020, having studied the matter since 2010, to facilitate access to credit from formal institutions for Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) that lacked sufficient collateral. In this type of CGS, the money for the Scheme is provided by the government through a state subsidy, but private entities manage the scheme. In case of a default, the guarantee is paid out of the government budget.

The Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) partnered with seven commercial banks in the scheme, which has made significant strides since its inception. By the end of 2023, 1,291 credit facilities totalling KShs. 6.18 billion had been disbursed to MSMEs. Notably, beneficiaries were small and medium enterprises and marginalised groups, including women, youth, and persons with disabilities.

In the FY 2022/2023 budget, the government allocated KShs. 1 billion to the CGS and KShs. 626 million to the Kenya Industrial Estates to help SMEs in manufacturing access credit.

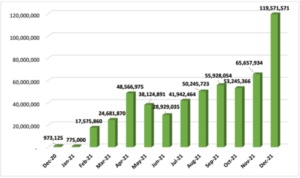

CGS utilisation by value (in KShs) in Kenya by December 2021

Source: National Treasury and Planning

While there is an attempt to give affordable loans to vulnerable groups in society, as well as MSMEs and SMEs in the country, it is clear that the reach is far from sufficient and continues to be limited to the confines of safety nets that ensure repayment. This

locks out a huge number of deserving individuals who may not have the wherewithal to belong to groups and are unable to access the loans in an individual capacity.

This highlights the need for further initiatives to broaden the scope of inclusive financing mechanisms beyond existing safety nets to cater to a more diverse range of aspiring entrepreneurs and vulnerable groups in society.

While the Kenya Kwanza Government has several revolving funds and a digital fund to support Kenyans access credit, the CGS is a useful tool that can be used by these existing funds to give guaranteed credit.

The Draft Credit Guarantee Policy is the outcome of this successful experiment and has been crafted to provide a solid legal and regulatory structure for the establishment of various Credit Guarantee Schemes. A dynamic financial environment in this realm will foster financial inclusion, leveraging credit guarantees in risk assessment to incentivize lenders to extend favourable terms to MSMEs. Moreover, it catalyses informal businesses’ transition into the formal sector, fostering collaboration with diverse institutions and ultimately stimulating investment.

The draft policy proposes an implementation framework where the Central Bank Government will be the regulatory institution with oversight of all CGS in the country. County Governments have been given the task of supporting capacity building and formalisation of MSMEs to enable them to access guaranteed facilities. The national government will come up with the legislation and attract investor programs while smoothing the business environment for MSMEs in the country.

In addition to the Policy, proposed amendments to the Central Bank of Kenya Act would accommodate the supervision of the schemes. Overall, both the policy and amendment set in motion the proliferation of these credit facilities to small, high-risk ventures in the country. It is up to technology firms and other institutions to find creative ways to play in the space set up by this regulatory framework.