Electoral reform agenda gets back on the table

Opposition boss Raila Odinga this week began piling the pressure on President William Ruto

that he hopes will culminate in a discussion at the negotiating table. His plan, according to a

media report, is to rally his supporters into mass action and civil disobedience.

Mr Odinga’s basis is the report by a so-called whistleblower at the Independent Electoral and

Boundaries Commission and his aim is to have electoral reform.

If he goes ahead, Mr Odinga would put Kenya back on the electoral reforms that followed the

General Election of 2007.

At the same time, Mr Ruto is reported to be mulling over a proposal to create a commission to

inquire over the events surrounding the announcement of the results of the General Election.

There has been speculation that the activity from Azimio is intended to counter the allegations

about interference with IEBC’s work.

As he left office, former IEBC chairman Wafula Chebukati asked the President to have an official

inquiry, suggesting that the events at Bomas of Kenya preceding the announcement of Dr Ruto

as winner were grave.

Mr Chebukati and former commissioners Abdi Guliye and Boya Molu this week testified at the

tribunal investigating the conduct of Irene Masit, the last of four commissioners who dissented

and alleged opaqueness in the processing of the results.

The former chairman, Prof Guliye and Mr Molu have repeatedly said that members of the

National Security Advisory Council and the Jubilee Party asked them to change the results and

that the latter even offered them a bribe. So great was the danger to their lives, they said, that

they had to go into hiding after the results were announced.

A commission of inquiry would be the official way to scrutinize the claims but it bears risks: a

protracted political process, the possibility of having to prosecute current and former civil

servants and senior officers in the security sector and the fallouts that would follow.

In the aftermath of the 2007 post-election violence the Kriegler Commission in its report posed

the questions: “Does Kenya belong only to politicians? Must the reports (everything) only be

looked at politically? Can the other players have a voice and be given space to be heard? What

about the consequences of impunity and inaction?”

These questions are valid in 2023 as Kenyans are treated to a spectacle of politicians arguing

over the 2022 elections and its validity four months after a president was sworn in.

Ideally, a fully composed electoral commission should be in office for two years prior to the

conduct of general or presidential elections. That means that Kenya now has two years, until

2025 to get things right in as far as electoral reforms.

While it was envisioned that hiring of IEBC commissioners would be staggered so as to ensure

continuity and institutional memory, Kenya is once again starting from scratch with Chairman

Wafula Chebukati and Commissioners Prof. Abdi Guliye and Boya Molu six-year terms having

ended, the trio of Juliana Cherera, Francis Wanderi and Justus Nyang’aya resigning and

Commissioner Irene Masit facing a tribunal.

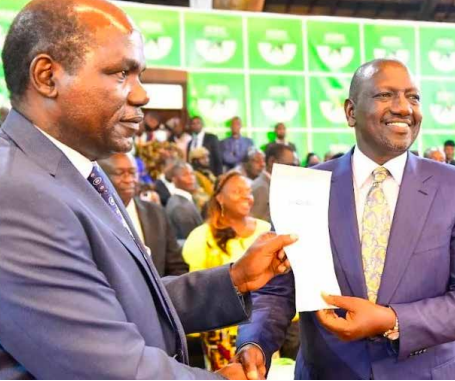

On Monday January 23, President William Ruto signed into law the IEBC Amendment Bill 2022

which outlines the process of recruiting new commissioners in the electoral body.

Signing of the bill into law means the allocation of the Parliamentary Service Commission

reduced from the current four to two (one man and one woman) out of the seven members of

the panel. The Inter-religious Council of Kenya will have two members, a man and a woman

while the Political Parties Liaison Committee, the Public Service Commission, and the Law

Society of Kenya will each nominate one member to the Panel.

Once the panel is picked and gazetted it will then consider the applications for positions of

commissioners, shortlist candidates and then conduct interviews in public.

After the process is complete, the panel shall forward two names for the chairperson and nine

names for the commissioner’s slots to the President after which the President is then expected

within seven days to send to Parliament the names of the Chairperson and six commissioners

for approval.

Some political observers have argued that the recommendations of the Kriegler Commission,

findings of a report titled ‘Electoral Law Reform in Kenya: The IEBC Experience’ and even

Supreme Court rulings have all comprehensively tackled the legal and operational changes that

should occur for better elections in Kenya. They have argued that the long-term solution would

be to implement the recommendations of the reports.

In his final speech as IEBC chairman, Mr Chebukati asserted that, “band aids such as

disbandment of the Commission that have been routinely undertaken have not led to a lasting

solution and that it is time the nation had a candid discussion on the electoral system that the

country should adopt to suit the circumstances of our country’s political anatomy.”

A commission of inquiry would offer an opportunity to have that candid discussion and perhaps

a long-term plan, but creates the possibility of diverting focus from his agenda for now, creating

a forum for political noise and the sort of activities that would slow down the economy in a

time of great need.