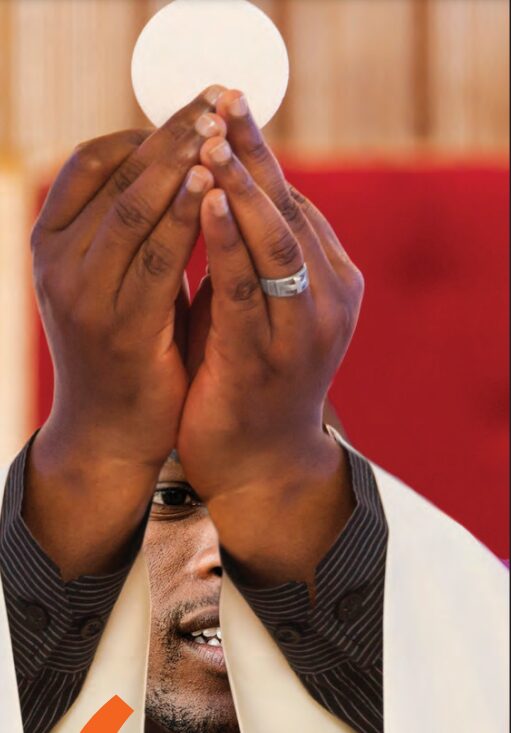

Church rattles the government months after being accused of being subservient to the political class.

“The church must remain a neutral entity free from political influence to effectively serve as a space for spiritual growth and community guidance.” – Catholic Bishop Philip Anyolo

The clergy has always welcomed senior top state officials to its pulpits. But now, as per the Catholic bishops’ statement earlier this week, it is singing a different tune, admitting that it was wrong to believe that God had chosen the Kenya Kwanza government for the people.

The clergy is now openly accusing President William Ruto and his administration of fostering an environment in which Kenyans have become accustomed to politicians’ lies.

Additionally, it has condemned President Ruto’s administration over unexplained killings, abductions, widespread corruption, and a growing culture of deception.

Since independence, religion, politics, money, and ethnicity have often been inseparable. For instance, during the 2013, 2017, and 2022 general elections, political competition was increasingly defined and characterised by the use of the notions of religion and tribe.

During these electoral processes or events, politicians appropriated biblical language and rhetoric and its imagery during campaign periods to paint their politics as God-driven and God-ordained while casting their antagonists politics as driven by the dark, evil forces of the devil and witchcraft.

Recently, Catholic bishops under their umbrella body – the Kenya Conference of Catholic Bishops (KCCB) – rattled the government after releasing a hard-hitting statement that reflected Kenyans’ frustration with the administration despite the two (Church and State) having a longstanding relationship.

The Catholic bishops’ statement voiced deep concerns over the country’s deteriorating social, political, and economic conditions, which have left many Kenyans disillusioned and financially strained.

In the recent past, Gen Z has accused church officials of being subservient to the political class – accepting hefty cash donations from lawmakers of dubious standing and the surrender of pulpits in many churches for use by politicians.

Kenya is largely a Christian-majority nation in which Christianity seems to be the de facto state religion. The 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census indicated that 85% of the country’s nearly 50 million people identify as Christians.

Among the population, 33.4% were Protestants, 20.6% were Catholics, 20.4% were Evangelicals, and 7% were from African Instituted Churches. Additionally, about 11% of the total population identified as Muslims, while other minority faiths constituted 7.6%.

The Catholic bishops’ statement, which inspired other mainstream churches such as the Anglican Church of Kenya (ACK), Presbyterian Church of East Africa (PCEA), and Muslims, rattled the government, forcing the Kenya Kwanza administration to react.

Government hits back

From the Cabinet meeting, the National Police Service, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education, and pro-government leaders all united against the blunt statement that condemned President Ruto’s administration for disruption of education, killings, femicide, runaway corruption, over taxation, anxiety and tension in the country as a result of political wrangles.

Anglican Archbishop Jackson Ole Sapit said the Catholic Bishops had reflected the feelings of a majority of Kenyans.

The latest sentiments from the clergy are backed by scriptures and express regret despite President Ruto’s persistent efforts to endear himself to the Church. Over the weekend, between November 15 and 17, the president attended three church events where he sought to mend fences.

Last month, in a surprise move, the founder of Faith Evangelism Ministries (FEM), Evangelist Teresia Wairimu, in one of her sermons, reflected on the church’s initial support for President Ruto, stating that their confidence had waned. “I have always been thinking that this government is a government of God; it is a government of fights.”

Evangelist Wairimu has been close to President Ruto and his family and has a long-standing relationship with former deputy president Rigathi Gachagua’s wife, Pastor Dorcas Rigathi, with whom she has evangelised for many years.

In 2022, during the State House dedication service after Kenya Kwanza’s administration victory, Evangelist Wairimu likened President Ruto’s humble beginnings to King David from the Bible, who rose from tending sheep to becoming one of Israel’s greatest Kings.

Even though the long ties between churches and political institutions currently seem to be fraying, the 2022 general election brought to the fore new power dynamics concerning the country’s churches’ relationships with politicians, especially in the case of William Ruto, his former deputy Rigathi Gachagua, and their spouses, both of whom are “born again” with significant influence in the country’s evangelical landscape.

Church and State

A study by the French Institute for Research in Africa (IFRA-Nairobi) authored by Utaguzi Haki, “Kenya’s Spiritual President and The Making of a Born-Again Republic: William Ruto, Kenya’s Evangelicals and Religious Mobilisations in African Electoral Politics, Ifri Studies, Ifri October 2024,” describes President Ruto as the first born-again president in the evangelical republic.

Haki, a scholar in residence in the USA and a policy and social analyst on religion, gender, and politics in the East African region, states that when Ruto decided to run for the presidency, he laid out a well-thought-out strategy to win the support of evangelicals and their huge constituency, estimated at 20.4% of the population.

During the electioneering campaigns, Ruto also received the support of the evangelicals movement and most key interlocutors of the Pentecostal and evangelical churches in the country.

According to Haki, some of the key interlocutors and gatekeepers of the evangelicals movement that vehemently supported President Ruto and framed him as God’s appointed ruler included Bishop Mark Kariuki of the Deliverance Churches of Kenya, Bishop Dr. David Oginde, former head of Jesus is the Answer Ministries (CITAM), evangelist Teresia Wairimu of the Faith Evangelism Ministries (FEM), and controversial Bishop cum politician Margaret Wanjiru of Jesus is Alive Ministries (JIAM).

Others were Bishop Arthur Kitonga of the Redeemed Gospel Churches of Kenya, Pastor Wilfred Lai of the Jesus Celebration Centres in Mombasa, J.B. Masinde of Deliverance Church – Umoja Nairobi, Reverend Kathy Kiuna and the late Bishop Allan Kiuna of the Jubilee Christian Centre (JCC), Bishop Harrison Ng’ang’a – Archbishop and founder of the Christian Foundation Fellowship of Kenya, and Apostle William Kimani of the Kingdom Seekers International – Nakuru, Bishop George Gichana of Deliverance Church Eldoret, and many other megachurches.

These clergies are not only influential in evangelical circles within the country, but many had the backing and loyalty of their large congregations. In addition, the author states that most of these megachurch clergy are also regarded as celebrities, respected televangelists, and opinion shapers, not just in their respective congregations but also in evangelical circles in Kenya and beyond.

For a long time, there has been an ongoing debate about the hefty cash donations politicians make to churches and individual clergymen and women in the country. There have also been debates about the impact of money on the relationship between the churches and the State and how the political class co-opts church leaders.

During President Daniel arap Moi’s regime, religious leaders like Archbishop David Gitari (ACK), Archbishop Raphael Ndingi Mwana a’Nzeki of the Catholic Church, and retired Reverend Timothy Njoya of the PCEA fought for democracy, freedom of expression and multiparty politics, have often been described as the architects of social justice and as the conscience of the country.

During the Moi era, religious leaders played a leading role in the struggle for constitutional reforms. Over time, they have argued that the constitution is the covenant of the nation and the ‘moral placenta’ of any meaningful democratic governance. With the recent events, should we expect the church to be the voice of the masses?