University funding model creates headaches, opportunities

The fate of Kenya’s tertiary institutions was one of the issues least talked about in the run-up to the General Election.

None of the main candidates seemed interested in addressing a problem that had been boiling since the number of students getting the minimum grade to join university started declining.

Fewer and fewer students joined the universities’ parallel programmes, and when COVID-19 forced many institutions to shut down or slow operations, public universities were left exposed. It was a prolonged low tide, and many were found to have been swimming unprepared.

Now, even as it works to recover from the shock of the Gen Z protests, the Ruto administration has rolled out a new funding model for university education.

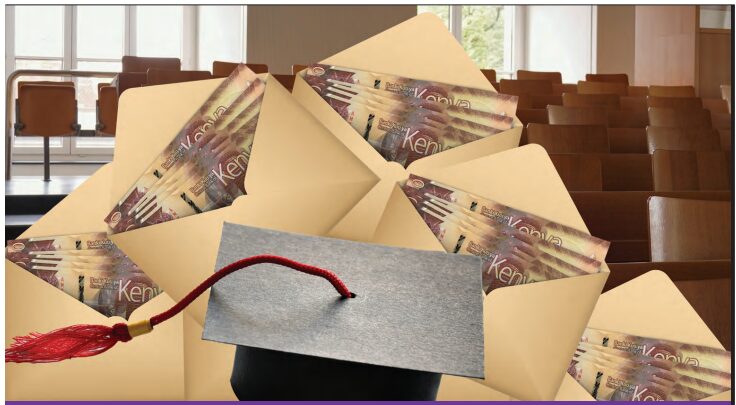

Under this new model, university education is financed from scholarships, loans, and household contributions without block funding from the Government in the form of capitation. Students’ scholarships will be based on their needs, which are assessed through a Means Testing Instrument. The instrument establishes the students’ ability by assessing their online submissions.

Unlike the previous model, where all Government-sponsored students paid the same in fees, the fees are based on the cost of the course.

A Medicine student, for example, is charged KSh600,000 per year, while a Gender Studies student pays KSh164,000 because some courses are more demanding in terms of staff and facilities than others.

With the new model, university education in Kenya has come full circle. From the days when students would receive pocket money, known in those days as ‘boom,’ they now graduate with sizeable loans.

The teething problems have created a new headache. Students complain that the Means Testing Instrument is putting them in the wrong economic bands.

President William Ruto has led a robust response, holding a televised town hall with university students represented by their leaders, who asked the tough questions and gave him a dose of the face-to-face criticism characteristic of Gen Z.

There have also been unsuccessful attempts to forestall protests in the major towns of Nairobi and Eldoret. Students are not leaderless, and efforts have been made to dialogue with them through official and unofficial channels, sending the message that the Government is determined to push through and deal with the teething problems.

Government officials have attributed the problems to basic errors, such as students leaving their applications with cyber cafe attendants to fill and inadvertently lying about their financial capabilities.

Some Government officials say that checks into the backgrounds of those who have gone on TV to complain have revealed that they attended relatively expensive academies, which shows that their parents or guardians should afford the new fees. Revelations like these belie the reality of the Kenyan education system, where parents with a decent income choose private schools for their children’s primary education. However, with few good private secondary schools, there is a stampede for admission to the good secondary schools, most of which are public.

Critics of the new model have persistently asked: What was old with the old funding model? The answer is simple: It was hard to sustain and resulted in the inability to pay lecturers, debts owed on statutory deductions, unpaid and unpayable pensions, and the continued deterioration of university amenities.

With the new model, Kenya is following the example of more developed countries. There are no free meal tickets, and those who qualify for university must figure out how they will fund their education. Scholarships, family funds, Government loans through the Higher Education Loans Board, and loans through other institutions will be the way forward.

Without guaranteed Government funding, universities will have to reorganise and fight for the best students. Universities will need to create the best programmes, hire the best professors, build the best facilities for the programmes, and attract the best students by building the best reputations for scholarships and job placement. Universities such as Strathmore, Aga Khan, and now Mount Kenya are well on the way.

This also creates opportunities for structured cooperation with the private sector, corporates and individuals backing programmes in universities and offering scholarships to the students.

For financial institutions, the model would perhaps open opportunities to create finance packages for families.

The reality for students and their families going forward is that they will need to plan better for tertiary education, especially in financing, which means they fundraise when the time comes, save for university like Americans save for college, and the reality of graduating with debt.