Which way forward Mr. President?

Introduction:

The country has been awash with analyses and sentiments over the advisory delivered by Chief Justice David Maraga on 21st September, 2020 with regards to the proposed dissolution of the Kenyan Parliament. The advisory to the President is anchored on Article 261 of the Constitution which provides for dissolution of Parliament in the event of its failure to pass the legislation required to implement the new Constitution.

Under Article 27(9) “the State shall take legislative and other measures to implement the principle that not more than two-thirds of the members of the elective or appointive bodies shall be of the same gender”. Thus the Constitution imposes this duty on the State as opposed to Parliament.

Most notably primary responsibility to legislate lies with the Parliament and not the State. However, the Executive can (and does) initiate and develop legislative proposals but in order for them to become laws, they must go through the legislative cycle which takes place in Parliament.

At the outset, it must be understood that what was delivered by the CJ was a recommendation and not a court order and so the President, in his capacity as Head of State and government, must determine how to move forward in a manner that upholds public interests and the best interest of the State and nation while protecting Kenya’s constitutional order.

So how did we get here?

Background:

Kenya has recorded a dismal record of women participation in leadership and decision making since independence. Although Kenya’s Constitution mandates that all appointed and elected bodies contain at least one-third women, women’s actual representation often falls short of that threshold. The Constitution fell short of providing a mechanism for actualizing this principle by failing to provide for the processes that will be followed to ensure that ‘not more than two thirds of either gender’ consists in the National Assembly and the Senate as is already provided for in the case of the County Assemblies in Article 177 of the Constitution.

It is this vacuum that led the women’s movement and other interested parties such as national organizations working for gender equality, and democracy issues to ensure increased participation of women in politics set out to seek a formula in good time before the 2013 elections to avoid a Constitutional crisis and the continued marginalization of women. At that point in 2011, proposals for how to achieve affirmative action for gender equality without amending the Constitution were considered and proposals were offered for public and policy debate nationwide which continued in early 2012.

The proposals were largely not accepted by various sections hence, it emerged that the most efficacious way to implement the principle of affirmative action was by introducing amendments to the Constitution itself, specifically regarding Article 97 and 98 of the Constitution via an amendment Bill in 2012.

This was not done. However, various amendments to the Elections Act and the Political Parties Act (PPA) were introduced which led to an improved regulatory environment. However, even so, the amendments lacked meaningful incentives and enforcement mechanisms with compliance among political parties being problematic.

Owing to civil society pressure and to avoid a Constitutional crisis the Attorney General on 8th October 2012, petitioned the Supreme Court to give an advisory opinion on whether Article 81(b) as read with Articles 27(4), 27(6), 27(8), 96, 97, 98, 177(1)(b), 116 and Article 125 of the Constitution of the Republic of Kenya requires progressive realization of the enforcement of the one third gender rule or if it requires the same to be implemented during the general elections scheduled for 4th March 2013. In its majority opinion, the Court acknowledged the, “social imperfection which led to the adoption of Articles 27(8) and 81(b) of the Constitution: that in elective or other public bodies, the participation of women has, for decades, been held at bare nominal levels, on account of discriminatory practices or gender- indifferent laws, policies and regulations. This presents itself as a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women in the Kenyan society and its resultant diminution of women’s participation in public affairs has had a major negative effect on the social terrain as a whole.”

Despite this, the majority of the Court was of the opinion that the one third gender principle as provided for in the Constitution could not be enforced immediately and was to be applied progressively: progressively being by 27th August 2015. The court stated that: “legislative measures for giving effect to the one third-to-two-thirds gender principle, under Article 81(b) of the Constitution and in relation to the National Assembly and Senate, should be taken by 27th August 2015.”

The court ruling created an avenue for the slugging of the Constitutional dispensation beginning with the party nominations/ primaries. 9,875 men managed to secure party nominations against 1,350 women. This was also as a result of poor party regulation and lack of proper operationalization of the revamped Political Parties Act and the Elections Act. This was reflected by the low number of women that were eventually elected during the general elections held in 2013 with only 16 women being elected as Members of Parliament out of 290 and only 68 being elected as Members of County Assembly out of 1,450. To cure this and comply with the Constitutional provisions on the not more than two third requirement, county assemblies had to nominate between 600-700 women which cost the country up to Kshs. 570 million (USD 6.7 million) per year now that the affirmative action principle was not achieved. It was estimated that this would jump to Kshs. 2.85 billion (USD 33.5 million) in the five years that covered 2013-2017.

Admittedly there were more women in the National Assembly as a result of the Constitutional provision on the reservation of the 47 seats but even with this additional number, the National Assembly was still short of the 117 needed to satisfy the one-third gender rule.

Women political candidates performed better in the 2017 general elections. Twenty-nine percent more women ran for office than in the previous election — a fact that led to the largest number of women ever seated at all levels of the Kenyan government. Women now hold 172 of the 1,883 elected seats in Kenya, up from 145 after the 2013 elections.

Further, women account for 23 percent up from 21 percent of the National Assembly and Senate — a figure that includes seats reserved exclusively for women representatives.

The election also saw three women elected as governors, a first for Kenya. Seven women became deputy governors, having been running mates of elected governors. Though deputy governors could be viewed as potentially a springboard to higher office, there is no clear guidance on the deputy governor’s role and authority. Office holders are not able to carve out specific roles and achievements that would allow them to better campaign on their own ticket. As a result, only two deputy governors from 2013 chose to run for competitive office and did not succeed.

At sub-national level, there were 747 women elected and nominated to serve as members of county assemblies (MCAs). The 2017 figures consist of 650 nominated women (87 percent of all the female MCAs) and 96 elected women (13 percent of all female MCAs). The 96 elected women MCAs were an increase of 17 percent from 2013. Nonetheless, a quarter of counties had no elected women MCAs, requiring all their women MCAs to come from nominated seats. These were: Kwale, Garissa, Wajir, Mandera, Isiolo, Embu, Kirinyaga, West Pokot, Samburu, Elgeyo Marakwet, Narok and Kajiado.

Why do these numbers matter?

It has been established that limited representation by women in Parliament results to minimal prioritization of enactment of gender related legislation and also women’s issues are likely to be defeated or trivialized in debates. This is as a result of extensive patriarchy in the decision making mechanisms in Parliamentary Committees and the House in the perception on gender issues and composition of these mechanisms. In addition, minimum priority is given to gender related legislation in the programme of parliamentary business drawn by the House Business Committee upon recommendation by political parties and individual members that have sponsored motions to be debated in Parliament.

The Legal Battle:

Following the temporary reprieve given to Parliament in 2012, it was expected that decisive action would be taken by 2015, in time for the 2017 elections. Following an order of mandamus by the High Court directing the Attorney General and the Commission on Implementation of the Constitution to “prepare the relevant Bill(s)for tabling before Parliament for purposes of implementation of Articles 27(8) and 81(b) of the Constitution as read with Article 100 and the Supreme Court Advisory Opinion dated 11th December 2012 in Reference Number 2 of 2012″

Despite Bills presented to it pursuant to that order, Parliament did not enact the required legislation prompting the filing in the High Court of another Petition-Constitutional Petition No. 371 of 2016, filed by the Centre for Rights Education and Awareness (CREAW).

After hearing that petition, the High Court issued another order of mandamus “directing Parliament and the Honourable Attorney General to take steps to ensure that the required legislation is enacted within a period of sixty (60) days from the date of [that] order and to· report the progress to the Chief Justice.” Parliament’s appeal against that decision was dismissed by the Court of Appeal.

Parliament, once again, failed to enact the requisite legislation thus provoking the six petitions by various interested parties. The gravamen of the six petitions is that Parliament having, for over 9 years and despite 4 court orders, failed, refused and/or neglected to enact the requisite legislation. As such among the prayers sought in the said petition was the invocation of Article 261 (7) and (8), thus offer advice to the President to dissolve Parliament.

Since the announcement of the recommendation by the Chief Justice, numerous pundits have offered varying opinions on the issue. However, there has been some relief following a ruling by Justice Weldon Korir who on 24th September suspended the implementation of Maraga’s advice pending further direction by the court, or the bench which subsequently takes up the matter after appointed by the Chief Justice.

How do we proceed?

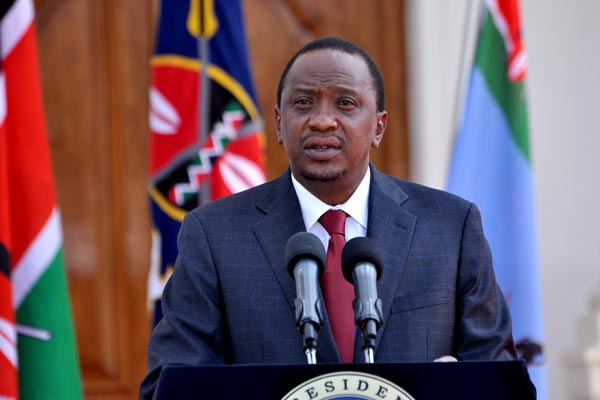

Some of those opposed to the position taken by the Chief Justice have opined that if the President were to dissolve Parliament this would cause harm to the State and constitutional order in terms of stability and efficacy. Others have stated that in some ways the CJ’s recommendation amounts to an open invitation to President Uhuru to subvert the Constitution through abrogation of a Parliament that has been duly elected by the people.

Meanwhile others have called for closer scrutiny of the electoral system as that is where the crux of matter lies as opposed to the composition of Parliament. Thus whereas Article 81(c) of the Constitution provides that the electoral system shall comply with the principle that no more than two-thirds of the members of elective public bodies shall be of the same gender, Articles 27(8) provides that “the State shall take legislative and other measures to implement the principle that no more than two-thirds of the members of elective or appointive bodies shall be of the same gender”.

Another argument provided is that even if the State were to take all legislative and other measures and they failed to result into a one-third representation of women in Parliament that fact would not render the composition of Parliament unlawful.

However, for many stakeholders and interested parties that have for 10 years endured and followed up on the matter, the advisory by the CJ was a moment in history worthy of a celebration. With the realization that another election is forthcoming in 2022, the Petitioners did not want to have yet another election being held that in essence would culminate in yet another “unconstitutional Parliament”.

What are the President’s options?

As the Head of State the President is the ultimate guardian of the Constitution and it is therefore incumbent upon him that before he takes the step recommended by the CJ he must do a cost-benefit analysis.

If the President were to declare the existing Parliament unconstitutional, thus dissolving it, it would lead to a by-election. However, there is no guarantee that a by-election would lead the 33% threshold being met unless proper safeguards at political party level were in place. Thus, Kenyans would suffer the political inconvenience and an expense of a by-election.

Then again, the President cannot simply ignore the arguments presented and recommendations of the CJ. Perhaps then, the best alternative would be re-consider some of the proposals provided in the 2011/12 affirmative action legislative proposal mentioned above to secure a middle ground that not only provides for a framework that ensures that the country not only adheres to the Constitutional provisions but also avoids such a crisis in the future.

Conclusion:

The passage of the new Constitution of Kenya finally offered the ‘breakthrough’ to addressing this systematic exclusion of women by enshrining the principle of equality of men and women in all spheres of life as a country and society. To actualize this principle, the Constitution provided for affirmative action measures that the State must embrace to lift women out of the current state of historical marginalization and exclusion.

However, in doing so, a more “tokenism” approach was adopted which not only goes against universal principles of suffrage but has proven not to be effective. There is therefore a need to look beyond “tokenism” and develop more democratic means of political participation.